Industrial Heritage

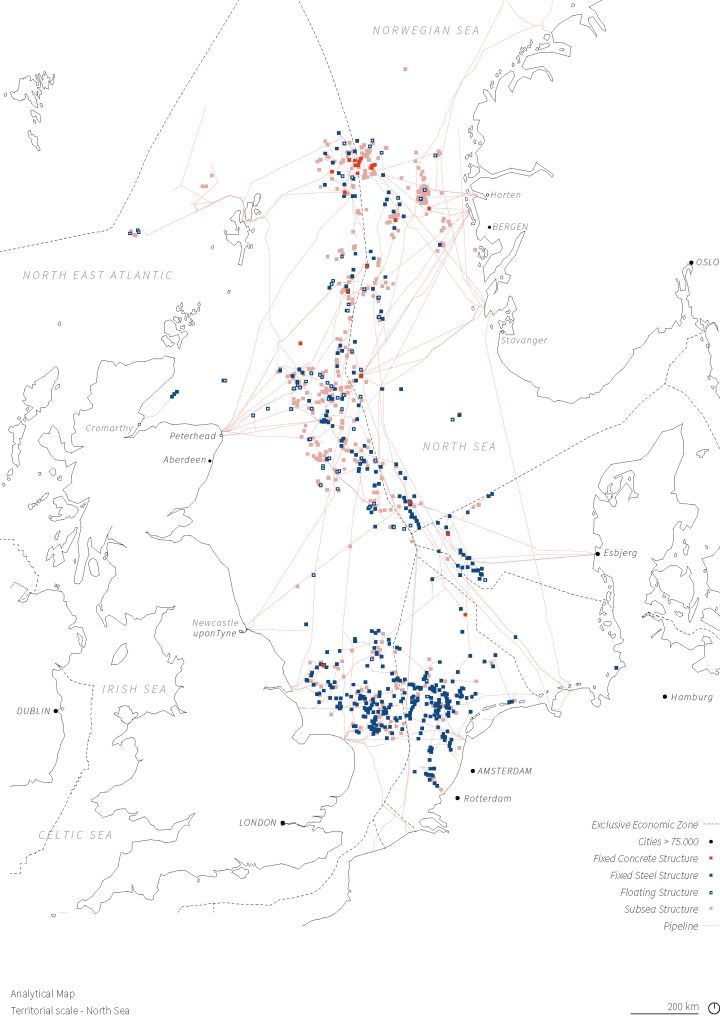

Almost invisible to society, one of the largest and most active industrial regions in Europe stretches across the entire North Sea, from the shallow shores of the Dutch and German coasts to the margin of the deep Norwegian Sea.

For almost 55 years now, operators have been exploiting oil and gas fields across the European continental shelf extensively. A vast network of 45.000 kilometres pipelines, including cables and other infrastructure, has been installed and more than 1350 offshore facilities are currently in operation in the North Sea, varying in size and construction type.

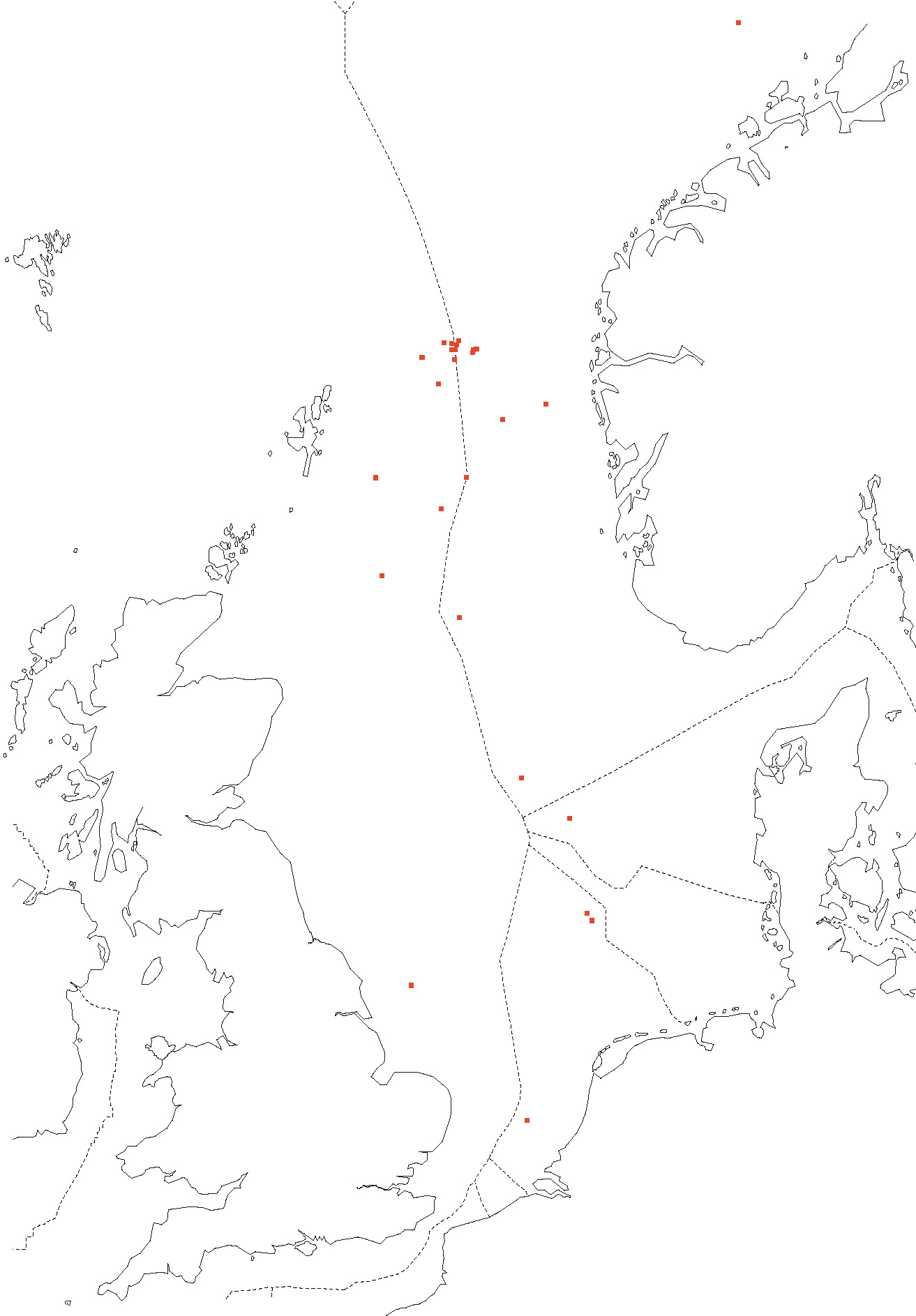

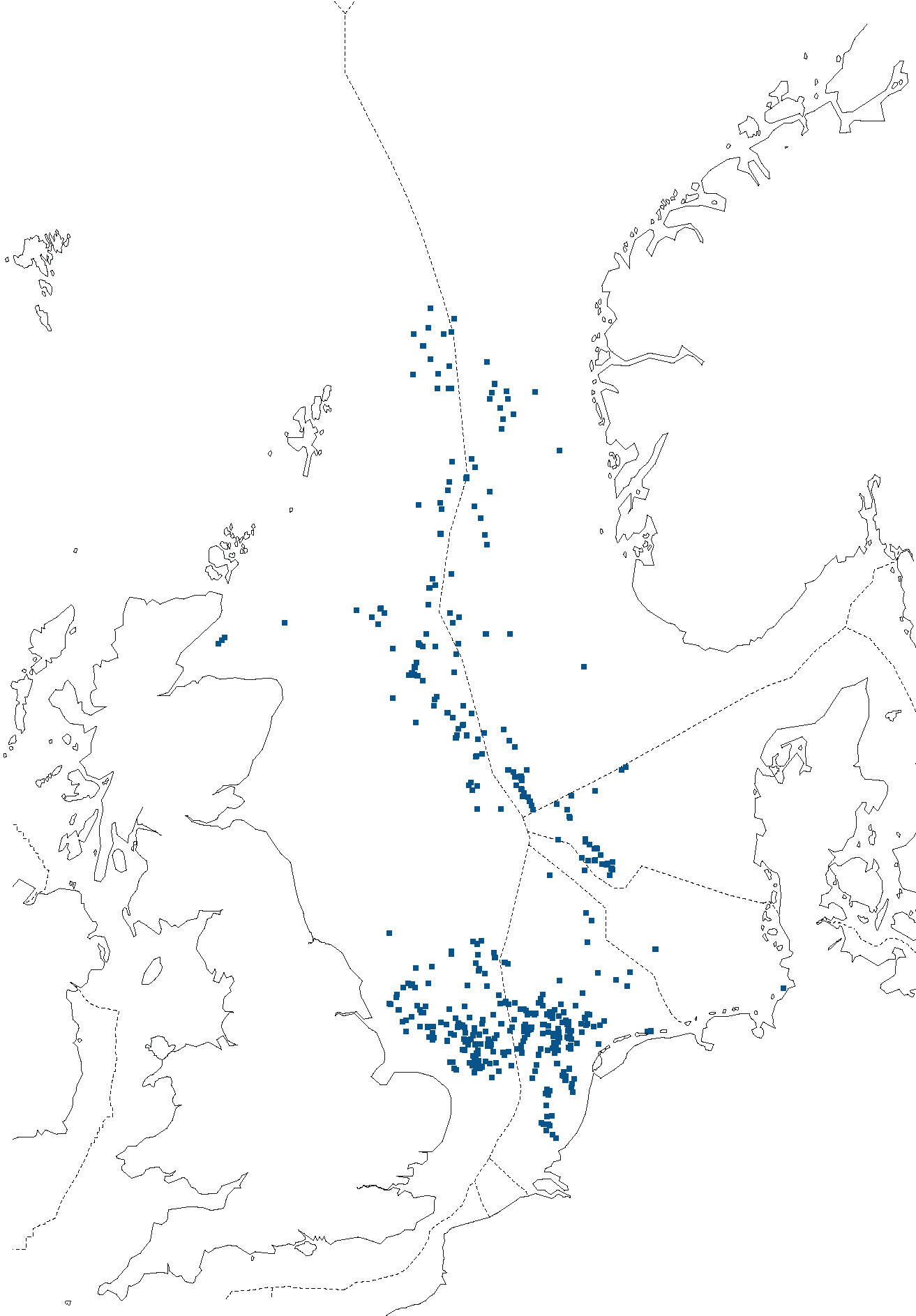

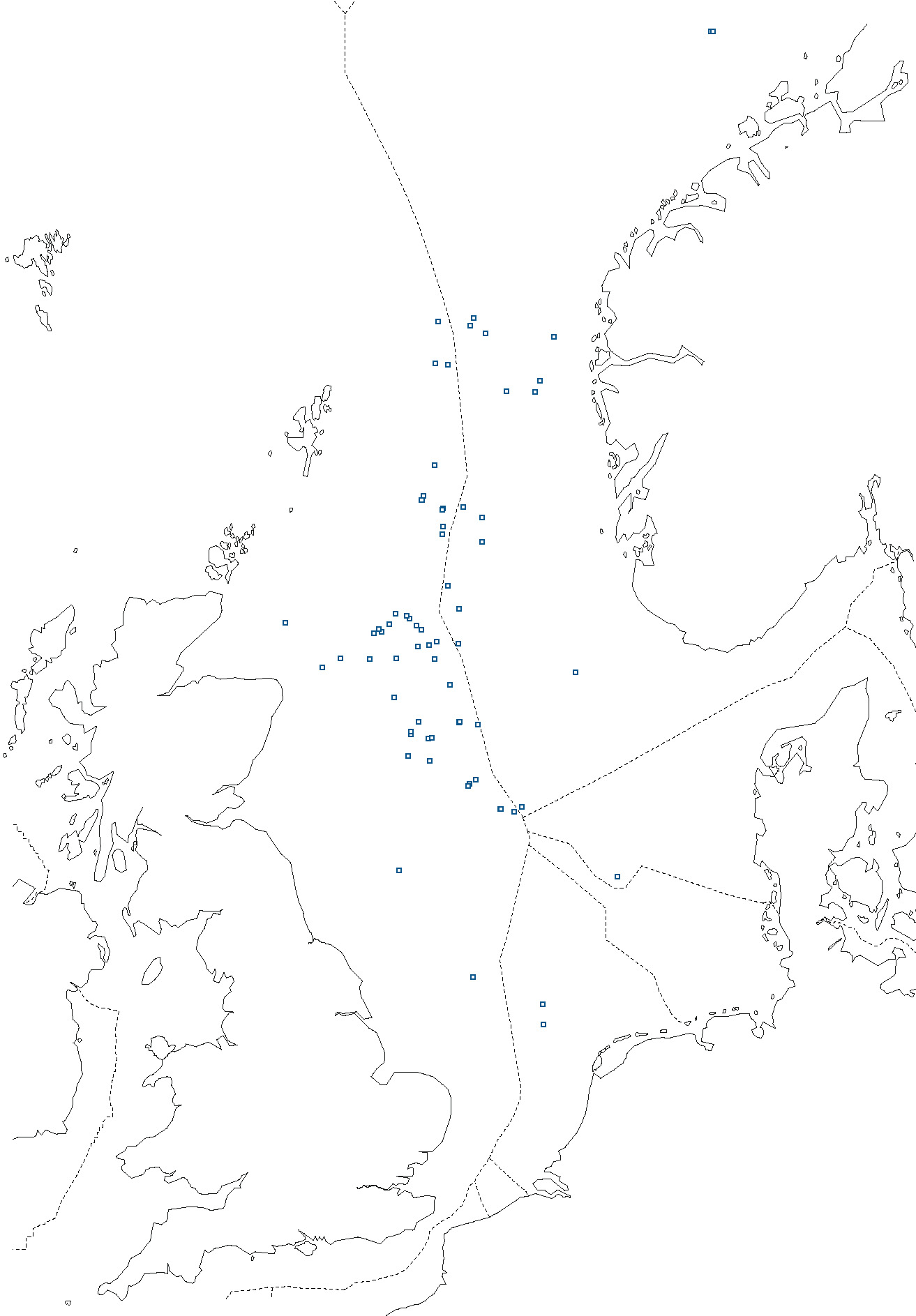

The analytical map illustrates the intensive use of the Exclusive Economic Zone of Norway, the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, Germany and Denmark for oil and gas exploitation.

Fixed Concrete Structures

The central and northern North Sea is mainly marked by deeper water and more exposed metocean conditions. The instalations found in this region are proportionally heavier installations. The majority of heavy concrete gravity base infrastructure can be found here.

Fixed Steel Structures

The southern North Sea, including parts of the UK Continental Shelf, the Danish and the Dutch Sector, is characterised by comparatively shallow water with less than 60 meters and relatively moderate metocean conditions. The prevailing gas resources are exploited with light steel installations.

Floating Steel Structures

The floating vessels are used preferred in frontier offshore regions or as solution for exhausting smaller oilfields, where seabed pipelines are not cost effective. They are remotely moved to new locations.

Subsea Structures

With over 800 installations, subsea structures make up the largest part of offshore facilities in the North Sea. They work autonomously directly on the seabed and can be found at any oil or gas field development. These type has no architectural relevance, but is presented here for the sake of completeness.

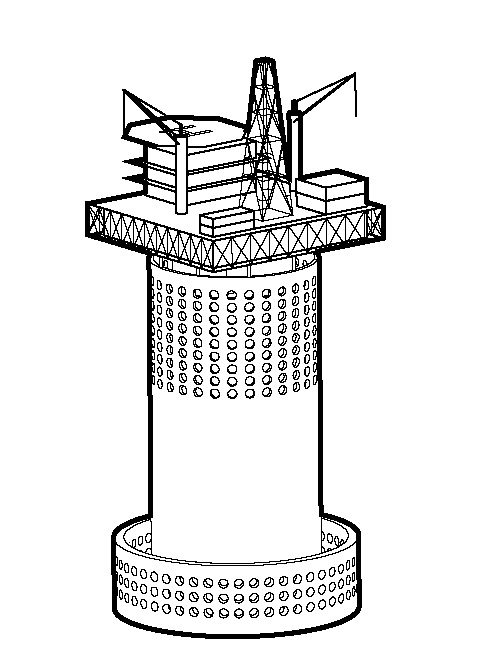

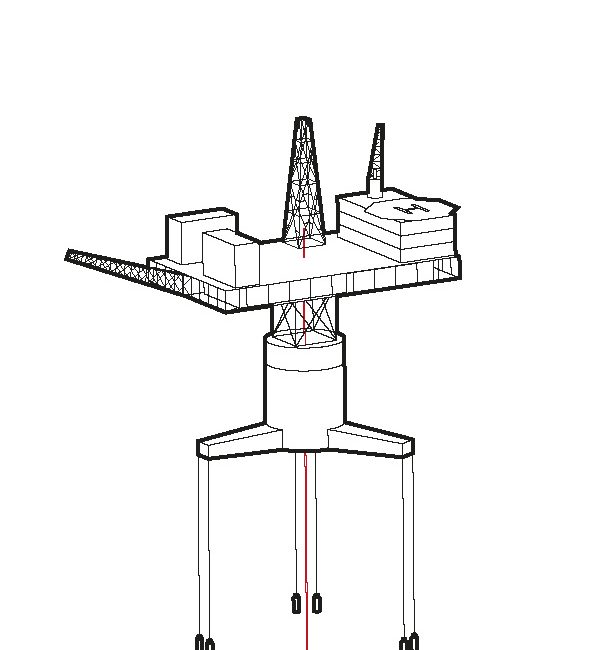

Doris Tower

The Doris platform is a cylindical gravity based tower platform made of prestressed post-tensioned concrete. Due to the heavy weight and the characterizing perforated breakwater wall, the tower does not need further anchores.

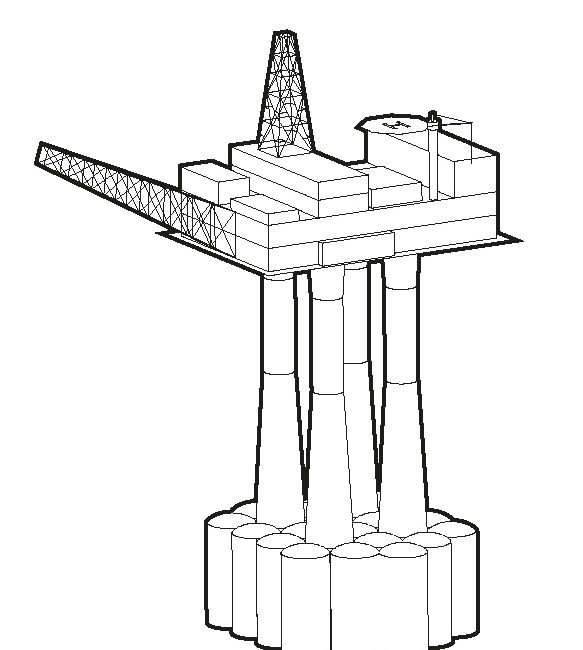

Condeep Structure

The steel reinforced and prestressed concrete foundation of the Gravity Base Structure, GBS in short, is a support structure held in place by gravity. The GBS have proved to be well suited in harsh offshore environments and stands out for environmental friendliness and low maintenance costs.

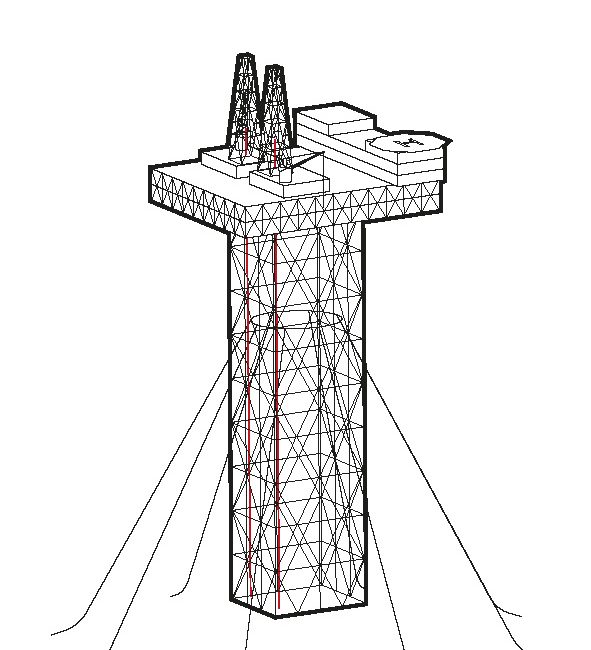

Compilant Tower

A compliant tower is similar to a traditional steel jacket platform. The structure extends from surface to the sea bottom and unlike its predecessor, a compliant tower is designed to flex with the forces of waves, wind and current. It uses less steel than a conventional platform for the same water depth.

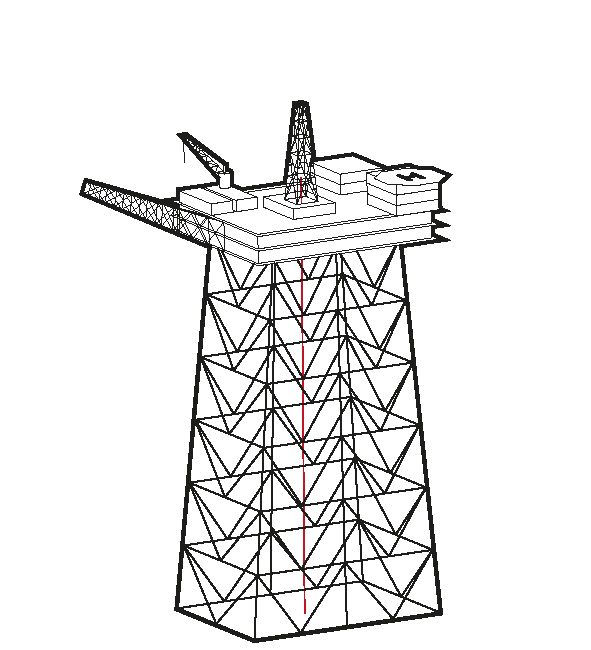

Steel Jacket

The steel jacket platform on a pile foundation is by far the most common kind of offshore structure. The jacket is fabricated from steel welded pipes, 2 meters in diameter, that penetrate 100 m into the sea bed.

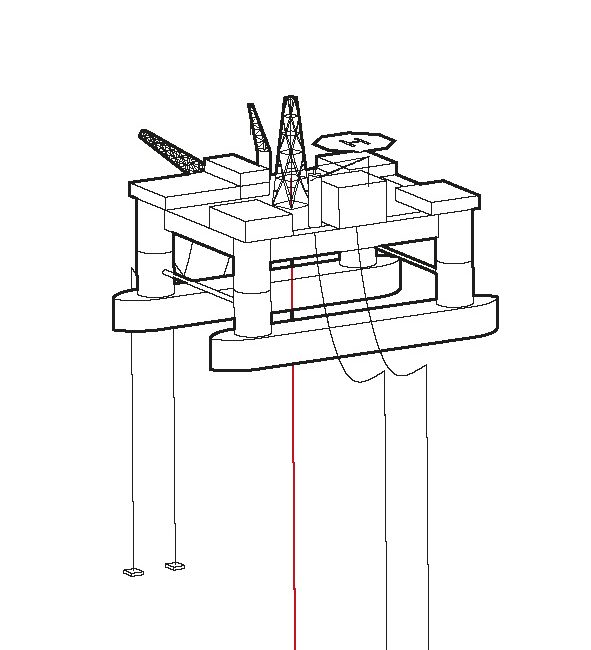

Semi-Submersible Platform

Semi-submersible facilities are as stationery floating hulls supported by pontoons that are tethered to the seabed with mooring lines. This configuration was considered desirable for relocating the unit from drilling one well to another. A Construction made of steel, as well as of concrete are possible for this type.

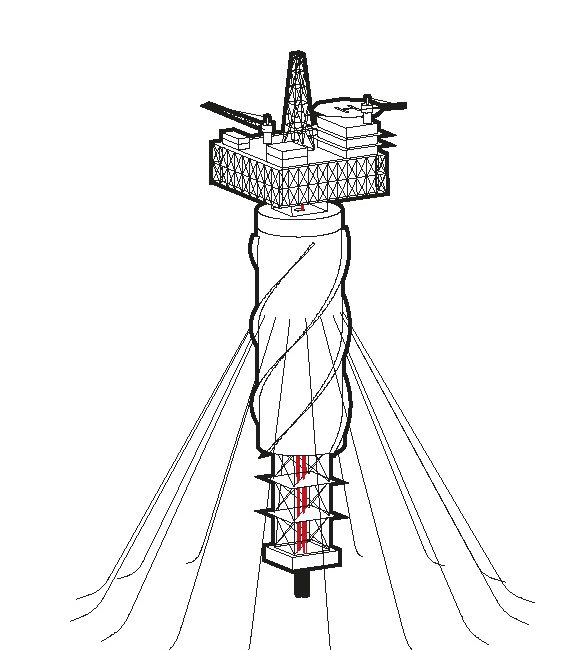

Spar Platform

The Spar Platform consists of a large-diameter single vertical cylinder, supporting a deck. It has a typical topside with drilling and production equipment, three types of risers (production, drilling, and export), and a hull moored using a taut catenary system of 6–20 lines anchored into the sea floor.

Tension Leg Platform

The tension leg platform is a type of fixed platforms. The vertically moored compliant platform is permanently anchored to the seabed by steel cables and concrete piles, which are tightened by partially flooding the buoyancy tank.

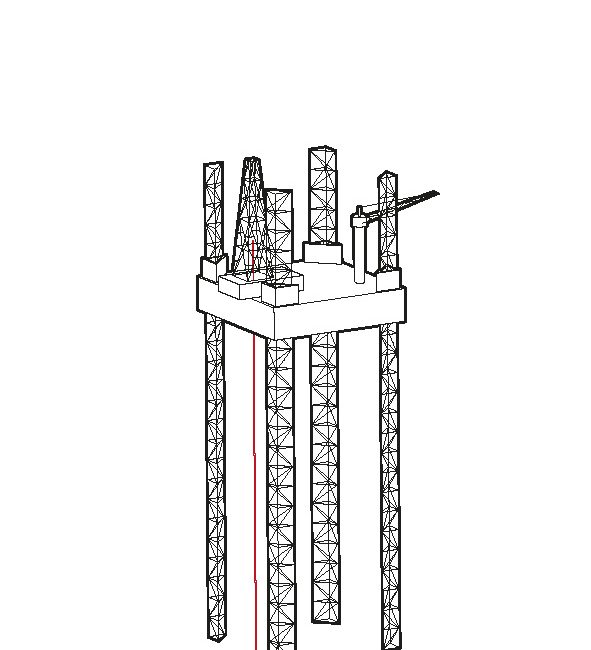

Jackup Rig

A Jackup rig is a type of mobile, self-elevating platforms. It consists of a buoyant hull fitted with a number of retractable legs that can be lowered down to the seafloor to raise the platform over the surface of the sea. The buoyant hull enables transportation of the unit to a desired location.

The discovery and exploitation of North Sea oil and gas has arguably been one of the most dominant episodes in the post second world war economic history of northern Europe.

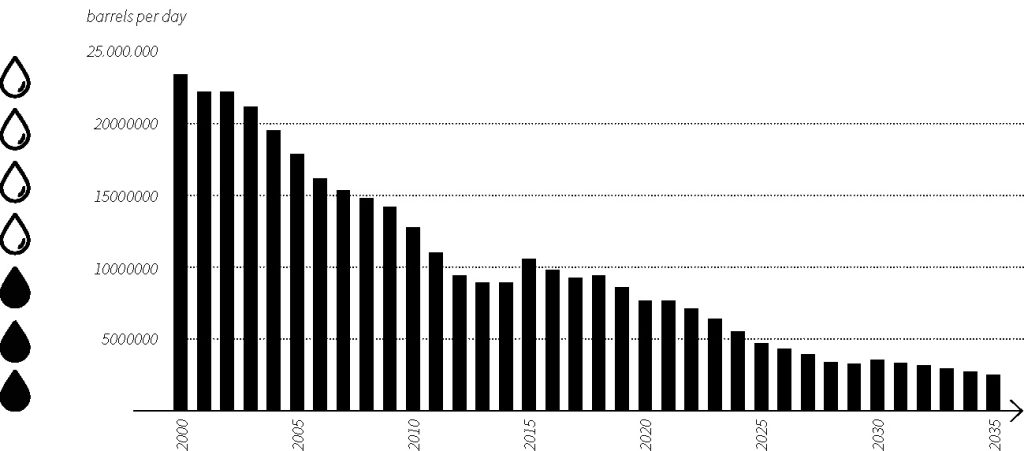

Production Forecast

Most of the producing fields are aging and production is expected to decline by five percent per year after 2022.

The forecasted production volume of the Brent, Forties, Oseberg, and Ekofisk field illustrates that offshore production has begun to decline rapidly since the early 2000s.

More than 42 billion barrels of oil and gas has been extracted so far, leaving a remaining potential of 24 billion barrel, equivalent to 35 years’ worth of production.

Currently, around ten percent of oil and gas platforms installed across the North Sea have been decommissioned and less than five percent of pipelines. However, many of these fields have reached the end of their productive live with the need for decommissioning. Since the industry is already closing more sites than it is opening, most of the North Sea Drosscape is expected to be gone by 2040.

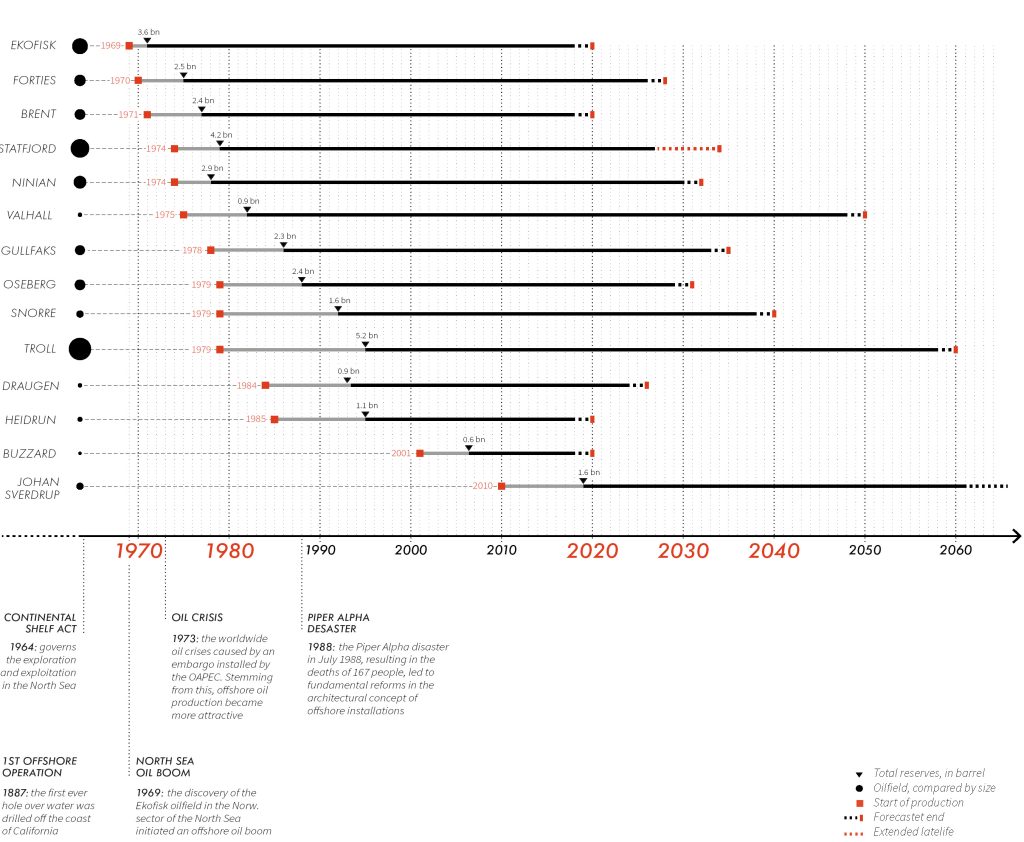

The bar chart illustrates the rapid evolving of the offshore development in the North Sea by means of the biggist oil field discoveries. The first decade of exploration between 1969 und 1979 was characterized by major discoveries of giant oilfields.

The find of the Ekofisk field in the central North Sea marked the beginning of the North Sea oil boom, followed by the Forties field in 1970 and the remarkable Brent oilfield finding in 1971, as one of the biggest in the UK sector of the Sea. The Statfjord discovery on the Norwegian sector in March 1974, was the largest single oil field find in the entire North Sea until recently.

Moreover, the chart demonstrates that most of the fields are forecast to be shut down in the near future, after decades of producing oil and gas. The iconic Brent oilfield, which is known as the backbone of crude oil pricing, has already dried up and the operater is about to plug the last remaining oil well. This draws the beginning of the end of North Sea oil. Over the next two decades many of the aging fields with rarely remaining resources need to be shut down.